The things we do with our eggs; reproductive health and genetic engineering

This op-ed in the New York Times set off a few of my warning bells. There’s the refusal of the authors to actually state their specific fears. There’s the recourse to a rhetorical doublespeak in which “we don’t know if it’s safe” is used as an excuse for not trying the studies that could determine safety. There’s the distinction made between reproductive tissues and other organs.

But basically, it is a partisan op-ed (possibly a redundant phrase) in an area where I think we need more candid discussion and dispassion. What are the boundaries of health, especially with regard to genetic diseases? When do we need to treat the disease, and when do we need to welcome the person?

The gist of the article, for those of you who haven’t read it, is that any technology that alters certain reproductive tissues or early embryos is highly morally suspect, if not evil. Don’t mess with eggs, sperm, or early embryos, lest ye bring down the wrath of GATTACA.

What does it mean, and what can it cure?

The technology that sparked this particular episode of scientific eschatology is something called mitochondrial manipulation techniques. Its helps some women who can’t have children – or can’t have healthy children – because something went wrong with their eggs. Sometimes this is inherited from their mothers, and they have a disease that they don’t want to pass on to their children. Sometimes this is age-related, and they miscarry frequently because their eggs are, essentially, “tired out”. The common thread is that the mitocondria — responsible for creating energy for the cell — aren’t working the way they should.

Especially in the latter case, women might go to an in vitro fertilization (IVF) clinic to try to have a child. And maybe that works a little bit better, but only because IVF fertilizes far more eggs at a time than a woman’s body would. In some cases, it still doesn’t work.

But we can separate out different parts of cells. One thing we’re great at doing is pulling out nuclei — self-contained bubbles in the center of cells that contain most of that cell’s DNA. We can mix and match nuclei and cells, essentially. (Side note: We can even do this by dumping mammalian nuclei into, say, frog eggs. When we do it, the mammalian nuclei start acting like they’re in stem cells.)

So you get an egg cell with healthy nuclei, and you take its nucleus away. You replace it with the nucleus from your patient’s egg cell. Then you proceed with IVF. You can get a healthy child this way. (Note: This technique has already been done, and healthy children have been born.)

In short: infertile women are going to IVF clinics, and altering their eggs to have healthy babies.

Why is that causing conflict?

Treat the disease, don’t change the child

The essential problem here, as best I can tell, is that the mother isn’t going into the doctor complaining of pain. She is most likely having trouble having children, but infertility is the only symptom this procedure treats in the mother. And the medical intervention (a mitochondrial transplant of sorts) will last with the child longer than the mother. So it seems to many like the intervention is, in a way, on the child’s behalf. It’s like noticing an embryo will likely have a disorder, and fixing it before the embryo is born.

That technology: to test a child for genetic traits and select only children without those traits has been well-used and also misused. Well-used in cases like Tay Sachs, in which miscarriages and babies who will die within months are sorted out from potentially healthy embryos. Misused in cases like sex selection, in which female embryos are passed up or selectively aborted in preference for male embryos, contributing to the overpopulation of males in countries like India and China. And there are lots of gray areas as well: perhaps Down Syndrome is the best example of this, in which a conclusive test for a life-long, untreatable, condition can lead to passing up embryos or selective abortions.

And at its worst, the analogy here spreads to horrifying things — eugenics things — like selective abortions of fetuses likely to be homosexual, or autistic, or brown-eyed.

The author takes a very strong stance against this: reproduction is a work of random chance. If you aren’t willing to play that lottery, you shouldn’t be a parent. And so if you need to change your gametes, or select out certain early embryos, you shouldn’t be a parent.

Whose Egg is it Anyway?

Here’s another analogy. I might notice, in the course of my life, that my body behaves differently than others’. For instance, perhaps I start noticing that I am constantly thirsty, no matter how much I drink. Maybe I start losing weight, and feeling hungry and tired all the time, no matter how much I eat. I’d probably go to the doctor. The doctor will run some tests, and may find that I have type I diabetes, in which certain cells in my pancreas have stopped functioning. They can’t produce insulin.

The solution is to help my body produce insulin. Right now that means regular insulin injections and carefully monitoring my blood sugar — doing the job of the pancreas for it. But the cell-therapy research being done to replenish insulin-producing cells in the pancreas of type I diabetics is lauded, and rightly so.

In short, if my pancreas stops working properly, it is strictly a good thing for medicine to help me fix it.

Let’s say instead that what I notice is that I can’t get pregnant. Again, I go to a doctor (most likely an IVF clinic) and they run some tests, and see that certain cells in my ovaries have stopped functioning. They can’t produce enough ATP.

Is the solution to help those cells produce ATP?

Fortunately, egg cells can function outside of the body. Fortunately, we have a procedure to replace the mitocondria in an egg cell, which would allow it to produce ATP.

Basically, this whole argument comes down to who “owns” the egg. If egg cells are a part of the mother, and replacing mitochondria is fixing something in the mother’s body, then it seems like there is a persuasive argument to alter them. Unless eggs, still in the ovaries (even before fertilization) somehow belong to the future humans they may, potentially, one day at least nine months in the future, with a lot of help and luck, become, then this doesn’t seem like much of an argument to me.

One Note on Slippery Slopes

For anyone who might care to argue “but this technology could be used for evil, so it should be out-right banned” — that is not how we talk about ANY OTHER TECHNOLOGY. Limit the number of people who can practice this? We already do — we call them doctors and we require years of training. Limit the circumstances in which it can be done? Absolutely. Put in gate-keepers and registration and have serious conversations about the “ethics” of the situation? I am all for that.

I would love to see a candid discussion about how the use of egg donations puts pressure on low-income women to undergo painful procedures and give up their chances at having children in order for high-income women to maximize their chances at having children. And this technology, at least for the present, requires a donated, healthy, egg. But of note is that this issue, which is very real, was not even mentioned in the original op-ed.

Instead, it turned into a moralizing argument about what women should be allowed to do with their own egg cells. And I think that there is altogether too much emphasis put on moralizing hand-wringing over the ramifications and ethics of what women do (medically or otherwise) with their own bodies.

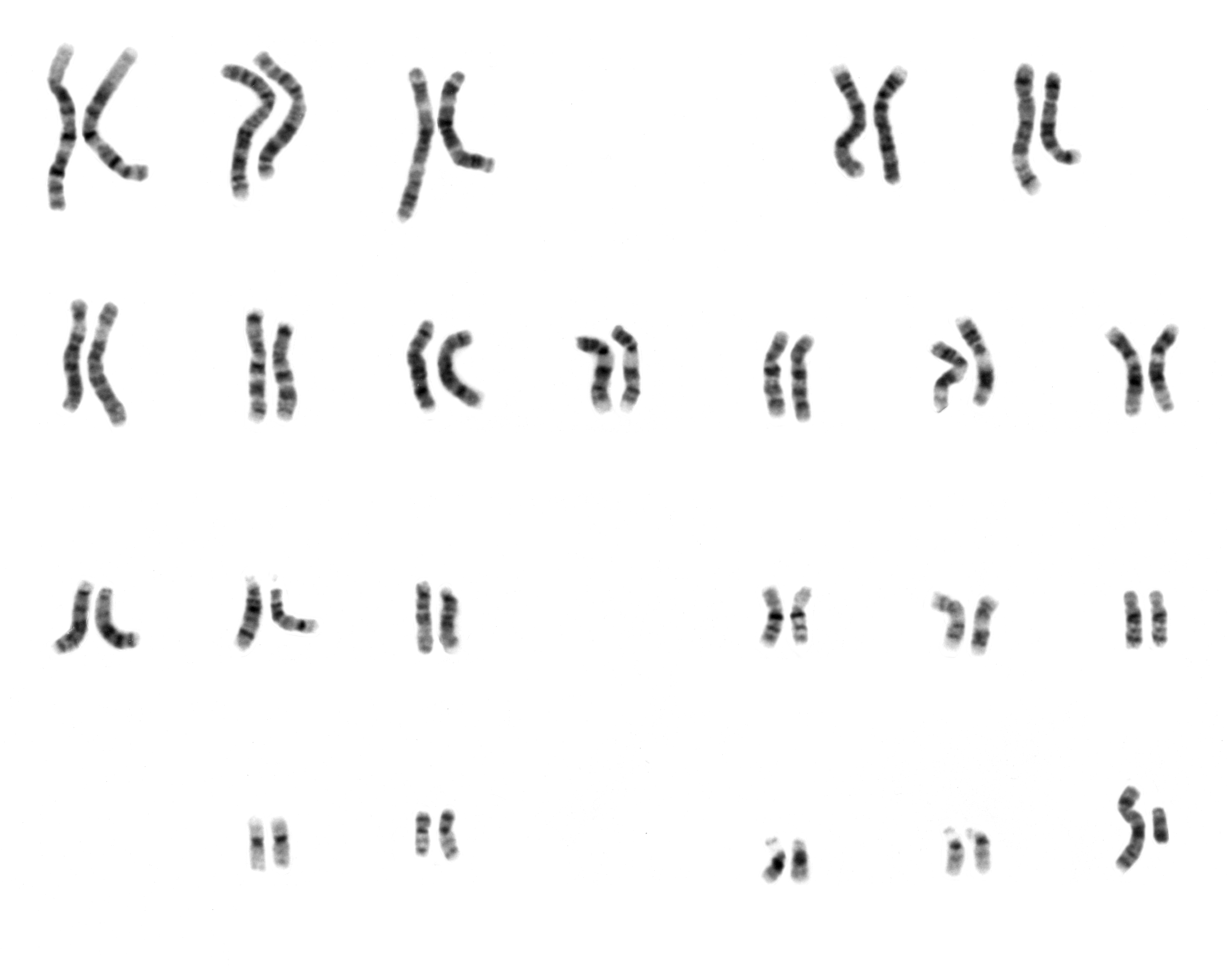

Featured image is of a blastocyst, By Harimiao (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons