I’ve been hoping for a while that I would come up with another idea for this series. And then Shireen Baratheon was introduced on screen, and I remembered that a ton of the most interesting work in genetics is done on viruses. And it all started to make sense. So, read on for an analysis of greyscale, and some talk about viruses and why they’re really freaky and cool.

For those of you who don’t know, in A Song of Ice and Fire, greyscale is a disease that is disfiguring but generally nonfatal if you have it as a child, and almost always fatal if contracted as an adult. Shireen Baratheon contracted greyscale as an infant, and it almost killed her, leaving her left cheek and most of her neck a mottled patchwork of stony grey and black skin. In addition, those who survive greyscale as children are immunized against the more severe form of the disease that afflicts adults. And finally, the wildlings (who, as far as I am concerned, are the most socially progressive and sensible clan in the books) consider the survivors of greyscale to be unclean, and treat them as if they are active carriers.

So, where am I going with this?

I’m not going to talk about symptoms. There is some argument about what real-world disease could most closely mimic the symptoms of greyscale, with answers ranging from calcinosis to diabetes to leprosy. Certainly, the symptom of “flesh turning to stone” isn’t something we see very often outside of magical universes. I’m also not going to talk about societal reaction: the societal reaction to greyscale is actually fairly similar to the treatment of lepers in the middle ages: isolation, tenuous suggested treatments, and general fear of the disease.

Instead, I’ll focus on epidemiology. In particular, a disease where a milder childhood form protects people from a more severe adult form: chicken pox.

Because in terms of epidemiology, greyscale works a lot like the chicken pox. And that means that purely in terms of what causes it and how your body reacts to it, we can think about greyscale by thinking about chicken pox.

So how does chicken pox work? Chicken pox is caused by a virus called varicella zoster. Varicella is airborne, and starts by infecting the upper respiratory tract before migrating to skin and mucosal layers – causing the itchy rashes. Your body reacts to the virus and creates antibodies, which generally stick around for the rest of your life. So if you’ve had it once, the next time you come into contact with varicella zoster, your immune system knows what’s what and stops it before you get a rash. This is what happens with a lot of viruses, and it’s actually how vaccines work: a vaccine is usually a weakened or dead version of the virus, that nonetheless cues your immune system to fight off the healthy, strong version you’d come into contact with in real life.

We often hear about diseases that are far worse for small children and the elderly: flu is like this, for instance. But what would make chicken pox more deadly in healthy adults? This is mostly speculation (a brief pubmed search didn’t turn up anything definitive), but as far as I can tell, there are a few factors. A history of lung disease, or smoking, can worsen the respiratory symptoms that are generally milder in small children who haven’t abused their lungs. A similar line of reasoning could be put forward for why symptoms are generally more severe in adults. But as far as I can tell, again, this is a fairly muddy area. In the case of greyscale, since it seems to mostly effect the skin, it could be that exposure to the harsh realities of life (especially, in the case of skin, the sun) weakens cells and makes them less resistant to infection.

![The color of these corn kernels is controlled by an ancient, virally-derived element. By Damon Lisch [CC-BY-2.5 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://madartlab.com/files/2013/05/PLoS_Mu_transposon_in_maize-1.jpg)

One complication with chicken pox is that it never really goes away. Instead, the virus infects dorsal ganglia (neurons) and lies latent there. As long as your immune system stays healthy and robust, it’s not really a danger: the virus won’t get reactivated from within those cells, and it doesn’t really cause any symptoms there. But in a lot of adults, your immune system sort of quiets as you hit 60 or 70, and this can result in a reactivation of the varicella virus that caused chicken pox when you were a toddler. This happens in about 10 to 20 percent of people. It’s called shingles. It’s more painful than chicken pox, and causes severe back pain in addition to lesions, but it’s not actually a new chicken pox infection – if you’ve never had chicken pox, you’ll never get shingles. And shingles isn’t associated with other complications of adult-contracted chicken pox, such as varicella pneumonia.

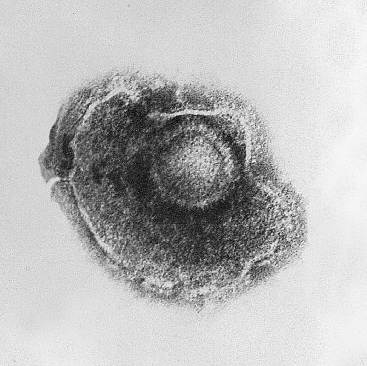

Again, this is in essence how a lot of viruses work: the symptoms might go away but the remnants of the infection are still there, lurking in some cell type or another. Herpes viruses (Varicella Zoster is a herpes-family virus) especially stick around and cause regular outbreaks because they go dormant. And in case that wasn’t weird enough, a good portion of your (yes, your) genome came about through EXACTLY that: it’s the skeletons of old viruses that hid in your ancestors’ DNA. Basically, we’re all made of viruses, and sometimes they can get reactivated.

And that’s essentially how the wildlings treat people with greyscale: at any moment, they could once again become contagious, and deadly to those around them. So in a certain way, it fits.

So what’s the take-home point? Well, not all viruses are quite like greyscale. But the vast majority are stealthy, determined bugs that leaves our DNA – if not our faces – scarred permanently. And while those scars do make our genomes interesting, it’s probably better to get the vaccine, and not the scar.